Pleural effusion is the ‘accumulation of serous fluid within the pleural space.’

In addition to pleural effusion, there may occur other kinds of collections in pleural space. The terminologies for these collections in pleural space are:

Empyema – accumulation of frank pus

Hemothorax – accumulation of blood

Chylothorax – accumulation of chyle

Types of effusion (based on their protien content)

Whenever you come across a pleural effusion case, pleural fluid is either Transudate or Exudate. The difference between the two is the high protein content in the exudative type.

Classification based on the protein content of pleural fluid is the most practical one. This is because, once you know whether pleural fluid is exudate or transudate, the causes and further workup/management is different for each group.

Transudative fluids have lower protein content.

These result from either increased hydrostatic pressure as seen in cardiac failure or from decreased oncotic pressure, as seen in liver or renal failure, nephrotic syndrome or malnutrition

Exudative fluids have higher protein content.

These result from increased microvascular permeability due to disease of the pleura or injury in the adjacent lung.

Causes

The causes of the majority of pleural effusions are identified by a thorough history, examination, and relevant investigations.

Pleural effusion causes can be classified according to the type of effusion as Exudative causes and Transudative causes of effusion.

Causes can also be grouped into common and uncommon causes.

Common causes:

-

- Pneumonia resulting in ‘parapneumonic effusion’ (exudative effusion)

-

- Tuberculosis (exudative effusion)

-

- Pulmonary infarction (exudative effusion)

-

- Malignancy (exudative effusion)

-

- Cardiac failure (Transudative effusion)

-

- Subdiaphragmatic disorders – subphrenic abscess, pancreatitis, etc. (exudative effusion)

Uncommon causes:

-

- Hypoproteinaemia – nephrotic syndrome, liver failure, or malnutrition (Transudative effusion)

-

- Connective tissue diseases particularly SLE & RA (exudative effusion)

-

- Post-myocardial infarction syndrome (exudative effusion)

-

- Acute Rheumatic fever (exudative effusion)

-

- Meigs’ syndrome – Ovarian tumor + pleural effusion (Transudative effusion – according to BTS)

-

- Myxoedema (Transudative effusion)

-

- Uraemia (exudative effusion)

-

- Asbestos-related benign pleural effusion (exudative effusion)

Clinical features

Symptoms

- Pleuritic chest pain often precedes the development of effusion, especially in patients with underlying pneumonia, pulmonary infarction, or connective tissue disease

- Breathlessness – Its presence depends on the size and rate of fluid accumulation

Signs

- Signs of pleurisy – Pleurisy causes an audible pleural rub. It is audible in patients presenting early, in whom effusion is either mild or has not yet developed.

- Signs of effusion – Interestingly signs of pleural effusion are elicitable in all four components of chest examination.

- Inspection – Tachypnoea, Reduced chest movement on the affected side

- Palpation – Reduced Expansion on the affected side. If the effusion is massive, the trachea and mediastinum may be pushed to the opposite side.

- Percussion – Stony dull note over effusion

- Auscultation – Absent breath sounds and vocal resonance over effusion. You may be able to hear bronchial breathing or crackles above the effusion surface.

Investigations

1- Radiological investigations

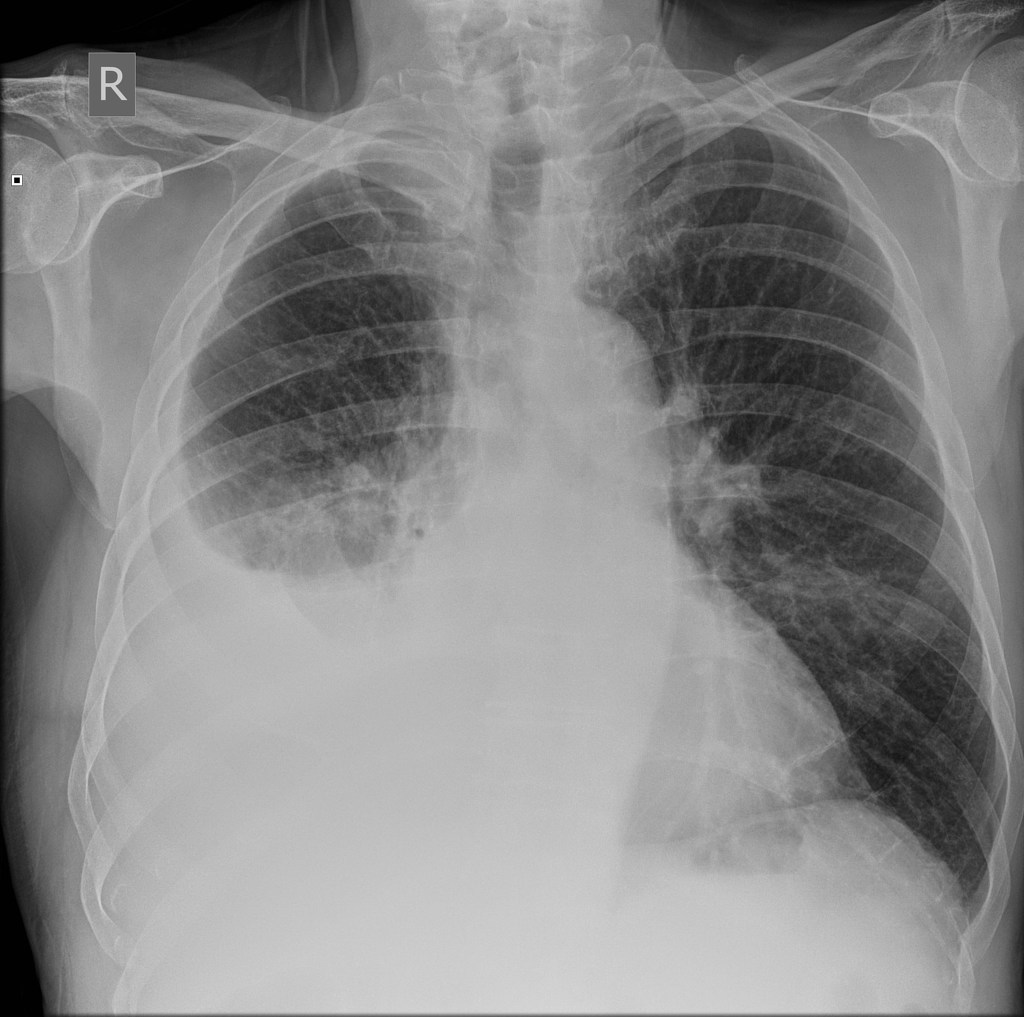

(i) Chest X-ray – PA view

The classical appearance of pleural fluid (on erect PA chest film) is of a curved shadow at the lung base, blunting the costophrenic angle, and the fluid meniscus ascending towards the axilla.

Around 200 mL of fluid is required to be detectable on a PA chest X-ray.

Previous scarring or adhesions in the pleural space can cause localized effusions.

Subpulmonary effusion, which is pleural fluid localized below the lower lobe, simulates an elevated hemidiaphragm.

Pleural fluid localized within an oblique fissure may produce a rounded opacity that may be mistaken for a tumor. This is called pulmonary pseudotumor.

(ii) Ultrasound is more accurate than plain chest X-ray for detecting the presence and then quantification of fluid.

A clear hypoechoic space is consistent with a transudate, and the presence of moving, floating densities suggests an exudate.

The presence of septation most likely indicates an evolving empyema or resolving haemothorax.

(iii) CT scan – It is indicated when a malignant disease underlying the effusion is suspected.

2 – Pleural fluid aspiration – for microscopy, biochemistry & cytology

In a few clinical situations where transudative effusion is the likely possibility, e.g., cardiac failure, a fluid tap for testing is not needed. In such situations, appropriate treatment of the underlying cause is administered first, and the effusion is then re-evaluated.

In other cases, however, diagnostic sampling is required.

After aspiration, appearance of fluid provides information on the color and texture of fluid. It can immediately suggest an empyema or chylothorax. The presence of blood is consistent with pulmonary infarction or malignancy but may result from a traumatic tap.

Biochemical analysis of fluid allows classification into Transudate and Exudate. Exudative effusion has protein content > 30 g/L while Transudative effusion has < 30 g/L.

– Light’s criteria is used for distinguishing transudate from exudate in borderline pleural effusion and shall be applied in fluid with protein between 25 and 35 g/L. According to these criteria, exudate is likely if one or more of the following criteria are met.

1. Pleural fluid protein to serum protein ratio > 0.5

2. Pleural fluid LDH to serum LDH ratio > 0.6, and

3. Pleural fluid LDH > two-thirds of the upper limit of normal serum LDH

Gram stain of fluid is done in parapneumonic effusions.

Cell counts and Cytology – The predominant cell type provides useful information on etiology such as neutrophil predominance suggest a bacterial cause. A cytological examination is essential to look for atypical cells in suspected malignancy.

pH – A low pH suggests infection, rheumatoid arthritis, ruptured esophagus, or advanced malignancy.

3 – Pleural biopsy – Ultrasound- or CT-guided pleural biopsy provides tissue for histopathological & microbiological analysis.

4 – Video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) – VATS can be done where necessary. It allows direct visualization of the pleura and direct guidance of a biopsy.

Management

Therapeutic aspiration is required to palliate breathlessness in larger effusions. However, removal of >1.5 L in one sitting is associated with a small risk of re-expansion pulmonary edema.

Before establishing a diagnosis, the effusion should never be drained to dryness. This is because a biopsy may become impossible until further fluid accumulates.

Treatment of the underlying cause – Underlying cause shall be treated, which will often be followed by the resolution of the effusion. e.g., treat heart failure, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, or subphrenic abscess.

How was this post?

Please share your feedback with us in the comments section below!

Feel free to download ppt and pdf of this post:

Download PDF & PPT

Some really prime content on this web site, bookmarked.

Thanks for the thoughts you are giving on this blog. Another thing I would like to say is that getting hold of duplicates of your credit rating in order to inspect accuracy of each detail would be the first measures you have to accomplish in credit improvement. You are looking to clear your credit profile from destructive details faults that ruin your credit score.

Thanks for sharing.

Great notes on pleural effusion quite accurate and practical. How I wish we demonstrated a technique for therapeutic pleural tap towards the end.

Good idea. Will try to update the post with this. Thank you!